http://www.mlb.com

August 13, 2012

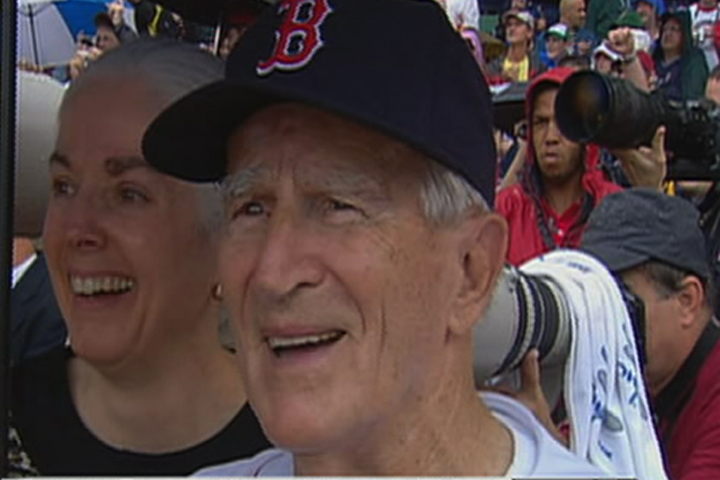

Gammons on Pesky's passing00:06:39

MLB Network analyst Peter Gammons talks about the passing of legendary Red Sox shortstop Johnny Pesky

A visitor to Fenway Park last summer asked, "What are the numbers up there on the right-field roof?"

He was told that they were the retired numbers of Red Sox Hall of Famers Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Carlton Fisk, Joe Cronin, Carl Yastrzemski ...

"And No. 6 was Johnny Pesky."

"Is he in Cooperstown?"

"No. He was a good player ... .307 lifetime hitter ... 1,455 hits. But with the possible exception of Ted Williams, he is the most popular player in the 100-year history of the franchise. He is certainly the mostbeloved.

"Then why is his number retired?"

"Because of who he is, not what he was."

I have never met a Red Sox fan who did not love Pesky. He always was nice to people because he was the essence of a good person. He went to rubber chicken banquets and Jimmy Fund events and loved his Red Sox as much as any fan out there. He played a year before going into World War II for three years, then when he came back played on those Red Sox teams that won one pennant in 1946 and probably should have won two more, losing the playoff to the Indians in 1948 and blowing a one-game lead with two to play to the Yankees in The Stadium in 1949.

He managed the Sox for two seasons in the '60s when the club was run like something out of "The Sound and the Fury," then returned as a broadcaster, a coach and the ambassador of everything Red Sox.

I always thought that one reason people liked him so much was that he never forgot from whence he came. Pesky didn't big league anyone. Yes, he played on some very good teams and was one of Ted Williams' best friends, but he never forgot that he started in baseball as a clubhouse kid in Portland, Ore. He shined Pacific Coast League shoes and washed uniforms and never forgot what that entailed, so if you worked the clubhouse or were an usher in the stands or were just somebody/anybody, he treated you with respect, enthusiasm and kindness.

Oh, there were times when he'd get a little piqued. Bernie Carbo once asked him if there were any pitchers "back in your time" who threw hard. Pesky shot back, "You couldn't have put a ball in play against Virgil Trucks or Dizzy Trout or Bob Feller."

And there was always the "Pesky held the ball" mark from the 1946 World Series. Enos Slaughter dashed around the bases from first base on a single and without television replays of today, the myth was that Pesky held the ball, allowing Slaughter to score.

What actually happened was that Dominic DiMaggio had been hurt and replaced in center by Leon Culberson, who was slow to the ball and getting the throw in.

"Lotta good that does me now," Pesky once said. "I was at an Oregon State football game, and some back for State fumbled a couple of times. Some loudmouth stood up and shouted, 'Give the ball to Pesky, he'll hold onto it."

He laughed. He told that story as a side dish at every rubber chicken event.

John and Ruth Pesky remained in Boston until each passed away, and were part of the landscape. Players loved having him in the clubhouse, and Jim Rice, who was exceptionally close to Pesky, told everyone that Johnny was the best hitting coach he ever had. He'd come to the clubhouse, dress at the locker right inside the door, and swap stories.

For many years covering the Red Sox for the Boston Globe, I'd go to road parks early, dress and work out. When players weren't hitting early, Pesky would work out what he called "Pesky's Silver Seven," comprised of broadcaster Ned Martin and three writers, Bob Finnigan, Chaz Scoggins and me. Oh, he loved to make us run after fly balls and play pepper so he could try to nail our ankles with line drives.

He always called me "My Captain of My Silver Seven." The last time I saw Johnny, this spring, he said "You're still my captain." Nice final words.

If you are out there across the country and do not understand why Pesky's funeral will be one of the largest of this century, first read David Halberstam's "The Teamates," the brilliant portrait of Williams, Dominic DiMaggio, Doerr and Pesky, who were first Red Sox teamates in 1942 and remained the closest of friends for the next 60 years, until Williams passed away in 2002.

"That doesn't happen in almost any walk of life," Pesky once told me, "especially our business of baseball. But Dominic, Ted and Bobby are three of the greatest men and greatest friends that ever walked the earth."

Seventy years ago, Pesky was a 22-year-old rookie with the Red Sox. Ted was 23, Doerr 24, DiMaggio 25. Hall of Famers Joe Cronin and Jimmie Foxx were on that team, in their mid-30's.

Sixty-three years later, when they held the Opening Day ceremony to hoist the World Series pennant above Fenway Park symbolizing the end of the 86-year drought, it wasn't David Ortiz or Pedro Martinez that pulled the rope to raise the flag, it was Pesky. On the day they celebrated their first World Series championship since World War I, it was a World War II hero who got the loudest ovation, who raised the symbolic end of the curse.

On the top steps of the visitors' dugout, Joe Torre, Derek Jeter, Don Zimmer and several Yankees stood and applauded Pesky.

"He's Johnny Pesky," Jeter said when asked about it in an ESPN pregame interview. "Of course you applaud, honor and respect Johnny Pesky. That's who he is to baseball."